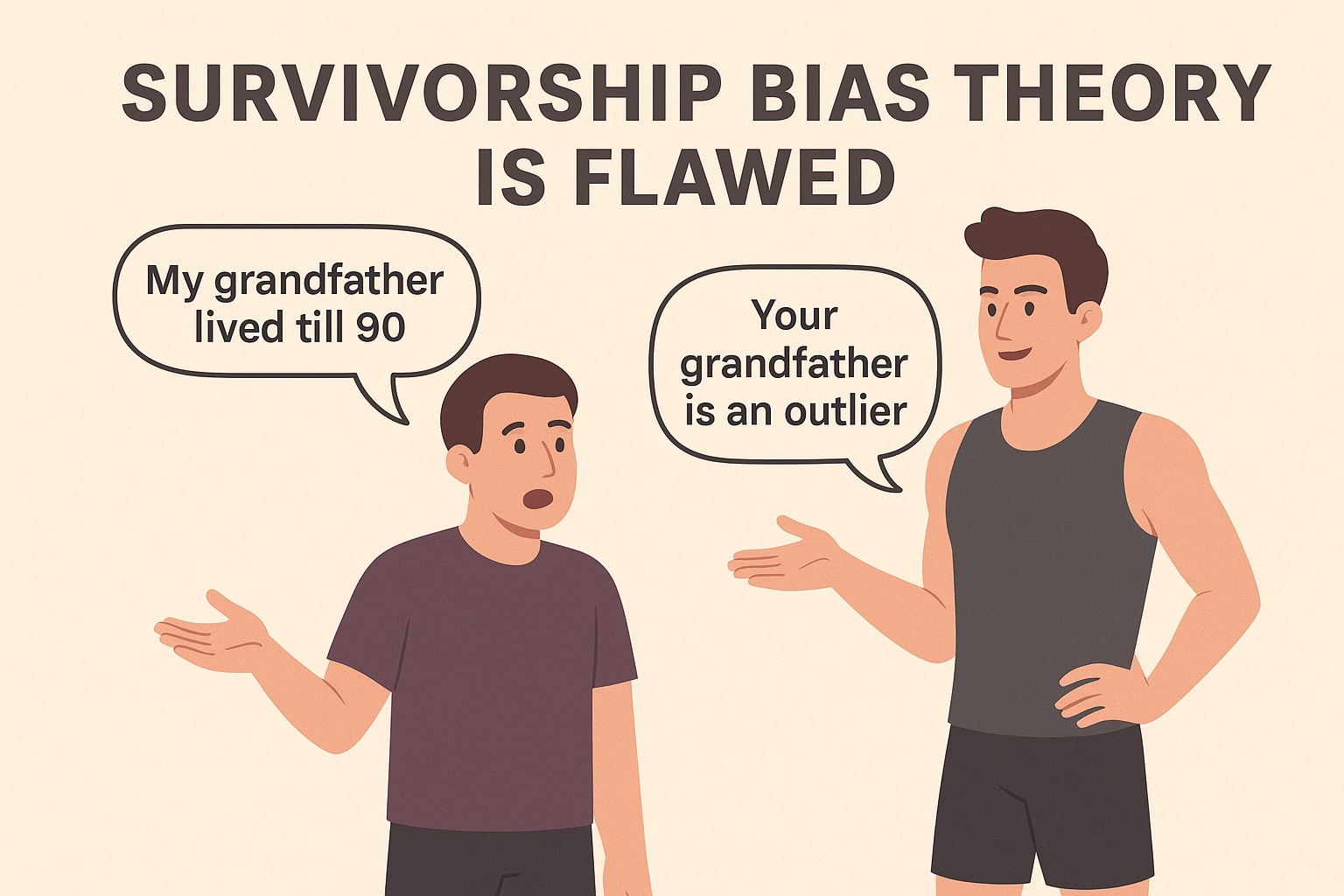

In health and lifestyle debates, one phrase pops up again and again:

“My grandfather lived till 90 without going to the gym or cutting out sugar.”

Almost instantly, a modern fitness influencer appears, armed with the survivorship bias theory.

They argue: “That’s an outlier. The average lifespan back then was just ~40, while today it’s ~70.”

Sounds smart, right?

Not really. In this context, the survivorship bias theory is meaningless. Let’s break it down.

Survivorship bias occurs when we only consider cases that have survived a selection process, while ignoring those that didn’t.

Classic example: looking only at successful companies and assuming their strategies guarantee success, without considering the many that failed.

But here’s the problem: applying this bias to health and longevity is misleading.

Fitness experts often highlight the low average age of earlier generations (~40 years) versus today (~70 years).

But averages can be deceptive.

Why? Because the causes of death then and now are completely different.

There’s zero overlap between the two.

So comparing averages across eras is statistically useless.

Instead of blindly quoting averages, we should look deeper:

👉 What was the average lifespan of those who did not die of communicable diseases in the past?

Chances are, it may have been comparable — or even better — than today’s lifespan.

Science helped us by reducing deaths from infections and diseases. But lifestyle diseases, born out of modern habits, have become the new killers.

This isn’t about romanticizing the past. It’s about not dismissing it as irrelevant.

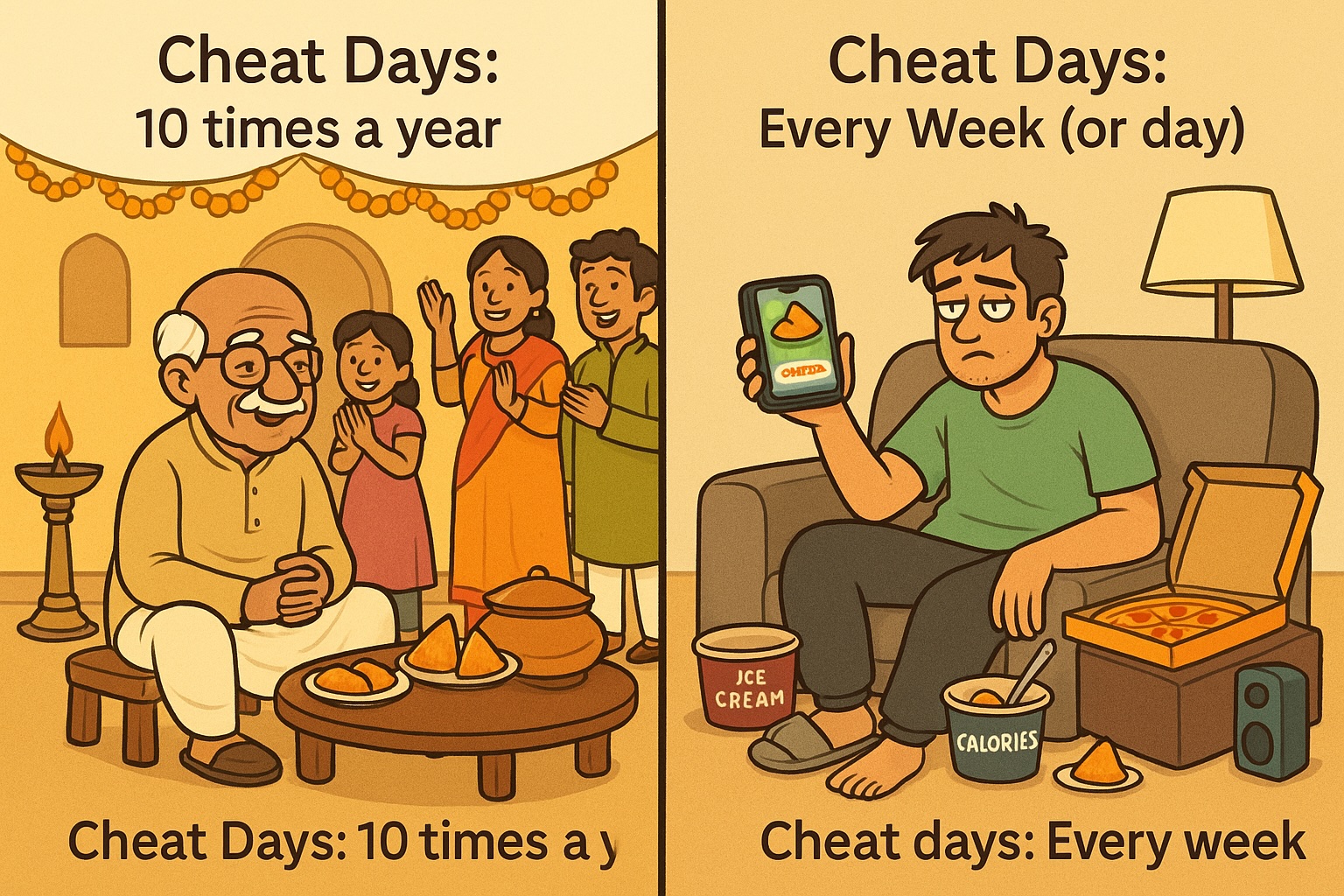

Our grandparents had their own wisdom:

Today, many of us struggle to limit even one “cheat day” per week. That contrast says a lot.

The survivorship bias theory sounds intellectual, but in lifestyle discussions, it falls flat. Different eras, different causes of death, different contexts.

So next time someone says “my grandfather lived till 90,” don’t dismiss it as survivorship bias. Instead, ask: what can we learn from the lifestyle patterns of those who lived long, despite the odds?

After all, ignoring real-world data just because it doesn’t fit a theory is bad science.